Malaysia has a rather odd way of celebrating excellence. In sports, where representing your country is a given part of the game (well, unless you’re from China), the government provides incentives in the shape of financial rewards, your occasional car or even a house, and eventually a Datukship. In some cases – most notably Datuk Nicol David and Datuk Lee Chong Wei – this is certainly well-earned.

However, in other fields where representing your country is distinctly not part of the game the governmental policy seems to be to wait till Malaysians have left for greener pastures and prospered, then to give them a Datukship in hopes of laying claim to a part of the fame they have achieved. Worse yet, using the term “Malaysian-born” for the ones who not only don’t live in the country, but who have opted for citizenship of another country. (And ironically, who would probably still be Malaysian citizens if the government allowed dual citizenship.) We see this in academics and scientific discoveries, and we see this in the celebration in the press of an exemplary Malaysian student in a Singaporean school, somehow without the obvious discussion of why a bright Malaysian mind would prefer to go across the Causeway. We see this more than ever in film – when’s the last time you saw Datuk Michelle Yeoh in a Malaysian production? – and with Shahrukh Khan, it seems we also want a taste of the fame of those who don’t even have a clue they’ve been given a Datukship.

And yes, this happens in the field of music as well. Don’t believe me? Just Google “Malaysian born” and see what you get.

To put it starkly: we haven’t built a proper arts academy, conservatory or school of the arts in the same way as one builds facilities for the development of sports. Instead, we wait till some other country has obtained our talent, very likely by way of having offered them scholarships, and then we ‘claim’ them with a Datukship. Something tells me that you don’t have to get a Ph.D. in order to call out this strategy for its dumbship.

I hear a voice at the back of my own head saying, “Whoa, hold on a sec, surely that’s going a bit far. After all, Petronas built this amazing hall, established the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra, and in more recent years put together a pretty decent national youth orchestra.” And there’s some truth in that.

But here’s the catch: when you define Petronas on par with the government, it opens up that policy to the same scrutiny you would give a country’s ministry of education. Which is quite different from whether YTL would prefer to fund the Kuala Lumpur Symphony Orchestra or the KL Performing Arts Centre; quite frankly, as a private entity and patron, YTL can do whatever it wants with its money.

If we choose to be ungracious about it, the whole MPO effort is short-sighted and non-sustainable, opting to rent an entity and label it as an achievement. Once the MPO toyed with the idea of an apprenticeship, but it seems even a rent-to-own system is asking too much.

If we choose to be gracious about it, the whole MPO effort has been akin to trickle-down economics. This all comes with the faith that when you put something there for the best, it will have a multiplier effect of sorts – one could say, a reverse approach of micro-financing. The idea is that when you inspire people by showing them the MPO’s international level, or bring together the best of Malaysian youth, somehow this will have a transformative effect on the nation as a whole.

One could say that as a concept it has some history of success elsewhere, with Dr Marc Rochester’s blog recently dealing with this to some extent. For whatever reason, however, it just has not worked in Malaysia. While we have gems of teachers like Miranda Playfair, who was known to have lessons with hours of bonus time, and Orsolya Korcsolan and Gergely Sugar, who gave free masterclasses in Penang, and Joost Flach, who has developed winds in Ipoh, we also have too many stories of MPO members who revel a bit too much in their expatriate status. There are too many stories of MPO members who circumvent the system of subsidized teaching through the organization in order to charge RM250 an hour privately for lessons which often go undertime. How many of these stories are accurate is indeterminate, but it did seem strange that a while back, it was insisted that the MPYO members provide the names of their teachers under the guise of forming some level of engagement and furthering a larger plan of music education. Being one of those teachers, I told my student that I didn’t expect even one email, and sadly my cynicism was proven correct, leading to my suspicion that it was a front for hunting down the MPO members who, for want of a better word, led to a black market in music education.

The larger point, though, is that the little island nation to our south decided instead to offer scholarships, bringing back newly-minted professional Singaporean musicians to their own country via bonds attached to those grants. And as I mentioned to Dr Marc, if both the MPO and the SSO were to face an untimely demise, there would be far more Singaporean professionals remaining, than Malaysian ones – not because of a lack of talent, but rather which magnet brought that talent on board.

The MPYO, unbeknownst to most of their members, is facing a similar issue. They can regard their orchestra as the elitist instution of their generation, or they can choose to take their new training as an obligation to not only trickle-down, but truly multiply the talents available in their hometowns. Not surprisingly akin to the MPO, there are examples of both of these, and in some circles the bad apples are indeed spoiling the bunch. In others, up-and-coming musicians are gaining the respect not only of their peers but of the generation before them. This fork in the road, above all else, will be the defining decision of today’s generation of aspiring musicians. Karma-like, it will determine how their own aspirations will be treated by those who established a foundation, well before the MPO began, and with lesser funding and far more challenges.

It comes down to this: when you build the Sepang F1 track, it doesn’t automatically make Malaysians into champion race drivers. It might work in places where the distance between Main Street and the race track are closer, and it is up to us to bridge that gap. This comes from institutions like Petronas, as well as the public in scrutinizing how their national property is utilized – and most importantly, the young musicians, deciding what their definition of talent really is: the ability to show, or the ability to share.

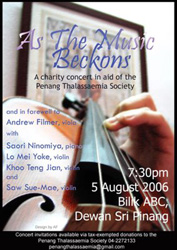

Andrew Filmer

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment